Program Report: Summer and Fall 2016 took members and friends of SYVNHS on a number of extraordinary field trips:

- An exploration of cultural artifacts, ancient and modern, at Vandenberg Air Force Base

- A full day’s immersion in the complex faulted geology of the Santa Barbara region, from multiple thrilling vantage points around the city and coastline with Jan Dependahl

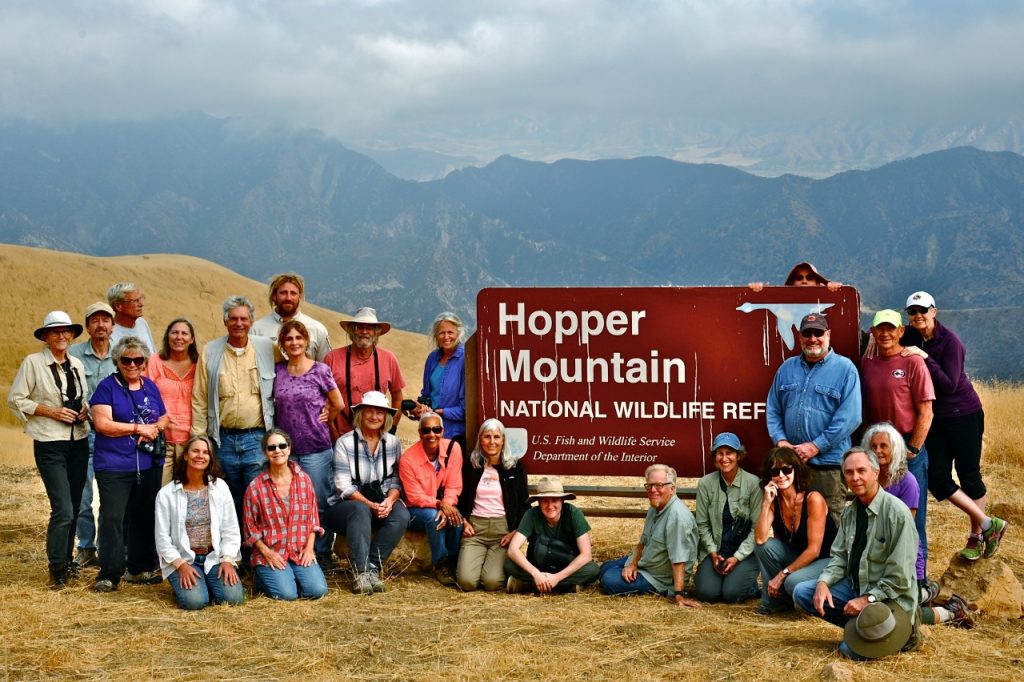

- A trip to the heights of Hopper Mountain National Wildlife Refuge with Director Joseph Brandt to view condors and learn about the ongoing heroic and successful efforts to stave off extinction for this species

- An in-depth look at the upcoming restoration of UCSB’s North Campus Open Space and Devereux Slough with Darwin Richardson and Dan Fontaine

- A multi-layered adventure around Morro Bay with author and renowned birder Joan Lentz and naturalist Larry Ballard, plus photographer Stuart Wilson and local tide pool enthusiasts

We are grateful to these generous experts for sharing their deep knowledge and enthusiasm with us.

Vandenberg Air Force Base

After a morning resonating to the mysteries of rock art from prior cultures and centuries, we visited the more recent artifacts at the Boathouse, which once housed personnel for rapid deployment in ocean rescues. Photos: Merrilee Fellows

The recently restored Boathouse near the southernmost point on Vandenberg AFB enjoys a gorgeous view south toward Point Conception, and hosts a nearby family of Great-horned owls.

Whose Fault is it? Geology of the Santa Barbara Area

Jan Dependahl led a trip as dynamic as the geology that forms Santa Barbara’s topography. From precipitous viewpoints on the Mesa, the Riviera and Elings Park, Jan showed us mountains lifting, synclines folding, and several faults splitting the westside, the eastside, the northside . . . . and the southside. We made 11 specific site visits. Photos courtesy of George.

From a private residence atop TV Hill, just on the Mesa fault that uplifts the sheer hill. Also visible: other blind faults and folds, many anticlines and synclines, Red Mtn. uplift, and the Montecito Overturn!

Jan demonstrates the angle of uplift. Several stops at the beaches revealed the Monterey formation and its unique oil-trapping structure, marine terraces, sloughs, and intriguing seaside anticlines.

At Elings Park (Godric Grove area, right), we viewed the massive San Antonio alluvial fan, plus many more faults including the Mission Ridge fault tying into the More Ranch fault that enters the ocean at Ellwood, where we walked across it later.

Hopper Mountain National Wildlife Refuge

Photos by Owen Duncan and, where indicated, John Evarts

It’s not all fun times at the condor holding pens – for birds or humans. Messy eaters. But if you want to avoid extinction, it means a short stint to have your blood tested for lead, and maybe cleaned of it.

Replica of a condor egg. Used for brief periods

to keep wild-nesting parents brooding when a

non-viable egg must be changed out for a

viable zoo-laid egg

Tiny radio transmitter and antenna attached to condor tail feather. All condors in the wild are outfitted with one of these sometime during their first year.

Director Joseph Brandt, (tallest figure at left, back row) for hours intrigued and educated this group, whose smiles reflect the many joys of the day. Photo: John Evarts

North Campus Open Space, Devereux Slough and Coal Oil Point Reserve

Darwin Richardson, SYVNHS board member, is a project manager for UCSB’s restoration project at North Campus Open Space, a multi-year project that will replace the former Ocean Meadows golf course with wildlife habitat, hiking trails for humans, natural wetlands, and wildlife corridors connecting Devereux Slough, Coal Oil Point open lands, and the Ellwood bluffs preserve. Darwin gave us a brief overview of the massive project, with many helpful maps and historical photos, showing how this former marshland was first filled and changed into a golf course. We toured the three reserves, finding more than 50 species of birds and exploring habitats from slough to mesa to shoreline.

Dan Fontaine, director of the Wilderness Youth Project, delves into the language of birds, and tells a darn good story himself. With him we saw and heard a rich bird population, including a rare female vermillion flycatcher, many hawks, ducks, shorebirds and herons. But besides seeing, Dan always asks you to ask: what, actually, are birds communicating, and to whom, and why? Spend enough time with Dan, and you may catch an echo.

Morro Bay and Montaña de Oro

From a trip participant: “Great day at some of my favorite places. It is an honor and a privilege to be in the company of magicians of the natural who can conjure up the mythological birds, beasts and critters that really do inhabit them.” Photo courtesy George

Bird revels: Joan Lentz guided us beside diverse flocks of shorebirds in the Morro Bay estuary. In the falling tide, feeding birds were abundant, active and vocal. Peregrine falcons made sudden thrilling passes. Joan ID’d for us 48 species here including avocets, wigeons, godwits, curlews, whimbrels, egrets, osprey, willets, white pelicans, dunlin, sandpipers, horned grebes, eared grebes, loons, cormorants, common goldeneye, bufflehead, terns and gulls. For all species, see Morro Bay Birdlist.

California Sea-Blite, Suaeda californica, has been extirpated from San Francisco Bay and is now found only in a narrow band around the edges of the salt marsh at Morro Bay. It is sensitive to any changes in hydrology.

Larry Ballard introduced the group to this and the other salt-and water-tolerant plants of the estuary. Photo: John Evarts

After a stop at Sweet Springs Reserve in Baywood Park with long scope-aided looks at a perching Merlin and 18 other species (complete list here), the group descended to Hazard Canyon Reef in Montaña de Oro State Park.

The extra-low tide exposed a rich mix of life-forms at Hazard Canyon Reef, including the extraordinary Gumboot chiton, largest chiton in the world. Photos: John Evarts

Larry Ballard and our tidepool experts Stuart Wilson, Dennis Sheridan, Marlin Harms and Jerry Kirkhart. They hold a Bull kelp stipe, Nereocystis luetkeana, fastest-growing annual organism on earth. Its stipe can grow up to 100 feet, topped with another 10 feet of fronds, all in about a year. Photo: John Evarts

Joan Lentz and Larry Ballard made this trip extraordinary with the wealth of knowledge they offered. Besides their generosity throughout the day itself, they later provided species lists of all the birds identified and many of the tidepool species seen. Please see Morro Bay Bird List and Montana de Oro Fauna List for complete lists.

This trip’s leaders, all “magicians of the natural,” did indeed call forth for us the almost-mythological inhabitants of marsh, reef, sky and sea, conjuring the day into something rich and strange.

Program Report: Coreopsis Hill, March 2016

Field Trip led by Larry Ballard.

Reported by Larry Ballard and Len Fleckenstein.

Photos and captions by John Evarts.

A rich dune habitat flora with many endemics (some quite rare) was in exuberant bloom on the north slope of Coreopsis Hill.

THE DUNES OVERVIEW by Larry Ballard

The Guadalupe dune sheet extends from Oso Flaco south to the Santa Maria River. It lies entirely on the Santa Maria River floodplain and represents two aeolian (wind-blown) Holocene dune-building episodes. The active dunes date from the present-day to about 2,000 years ago. The stabilized dunes date from 2,000 to 6,000 years ago. Larger aeolian dune sheets known as the Orcutt sand extend inland to Burton Mesa and La Purisima Mission. They date from the late Pleistocene about 25,000 to 80,000 years ago or likely even earlier. Some of this sand has likely been reworked by river and streams along its eastern boundary. Farthest inland is the Careaga sand. It’s not an aeolian sand but a marine sand, the remnants of a shallow sea dating from the Pliocene about 3 to 4 million years ago.

The older stabilized Holocene dunes (left side of photo) are well vegetated. The younger unstabilized Holocene dunes are on the right (west side of dune system) and support very few plants.

TRIP SUMMARY by Len Fleckenstein

Larry Ballard led this outstanding botany-focused hike in the unique setting of the Guadalupe-Nipomo Dunes National Wildlife Refuge. The coastal dunes refuge is at the western end of the Santa Maria River basin, north of the river’s mouth and about a mile south of Oso Flaco Lake in southern-most San Luis Obispo County. The dunes were at their seasonal floral peak after recent wet weather. The previous day’s rainfall provided easier footing on the sandy surfaces, although steep dune slopes posed challenges — and some fun. We started the hike from the farmland flats at the Beigle Road entrance (with special permission needed to cross through this private property) and soon entered the Refuge’s older, stabilized and heavily vegetated dunes. Then we hiked on to the younger, unstable and less-vegetated dunes dating from the more recent Holocene period. After about one mile, the group reached its target site, Coreopsis Hill, in view of the ocean and the most active dunes closest to the shore. We stopped for a lunch break amid wildflowers before heading back. It was notable that we saw a Sonoran Blue butterfly, a species that has not been reported from in this dune habitat according to Larry.

Giant coreopsis is no longer in the Coreopsis genus; it’s now Leptosyne gigantea. These stands on Coreopsis Hill are at the very northern edge of the species’ range

Larry, center left in green shirt, showed the group this hillside with an abundance of dune wallflowers.

Dune larkspur, Delphinium parryi ssp. blochmaniae, is an endangered subspecies named in honor of early-day school teacher Ida May Blochman. The primary stands we saw were on the north side of Coreopsis Hill.

A double-curiosity on Coreopsis Hill is its tiny stand of brown-spined prickly-pear cactus, Opuntia phaeacantha, adorned with patches of foliose lichen! This is part of a small disjunct population in northern Santa Barbara and southern SLO county. This plant’s main distribution ranges from transmontane California east to western Kansas. The Guadalupe Dunes have the northern-most patch of this cactus that has, as Larry put it, “an ocean view.”

Crisp monardella, Monardella undulata ssp. crispa, grows on unstabilized dunes (and also on more stabilized dunes). It ranges only from Oceano to Vandenberg AFB — and, no surprise, is considered an endangered species. We saw its more fragrant relative, San Luis Obispo monardella, on stabilized dunes, where its range is also very limited.

Dune wallflower, Erysimum suffrutescens, is a perennial that is widely scattered through the stabilized dunes — right up to the edge of unstabilized dunes.

The dunes were still wet from the recent rains, and their streaked surfaces were a reminder of how they serve as large reservoirs of moisture.